Lecture 2: Inference Systems and Selection Functions

Laura Kovács

Inference Systems

- Inference has the form , where and are formulas.

- The formula is called the conclusion of the inference;

- The formulas are called its premises.

- An inference rule is a set of inferences.

- Every inference is called an instance of .

- An Inference system is a set of inference rules.

- Axiom: inference rule with no premises.

Inference System: Example

-

Represent the natural number by the string

-

The following inference system contains 6 inference rules for deriving equalities between expressions containing natural numbers, addition () and multiplication ().

-

-

-

-

-

-

Derivation, Proof

- Derivation in an inference system : a tree built from inferences in .

- If the root of this derivation is , then we say it is a derivation of .

- Proof of : a finite derivation whose leaves are axioms.

- Derivation of from : a finite derivation of whose every leaf is either an axiom or one of the expressions .

Examples

For example,

is an inference that is an instance (special case) of the inference rule:

.

It has one premise, , and the conclusion .

The axiom

is an instance of the rule

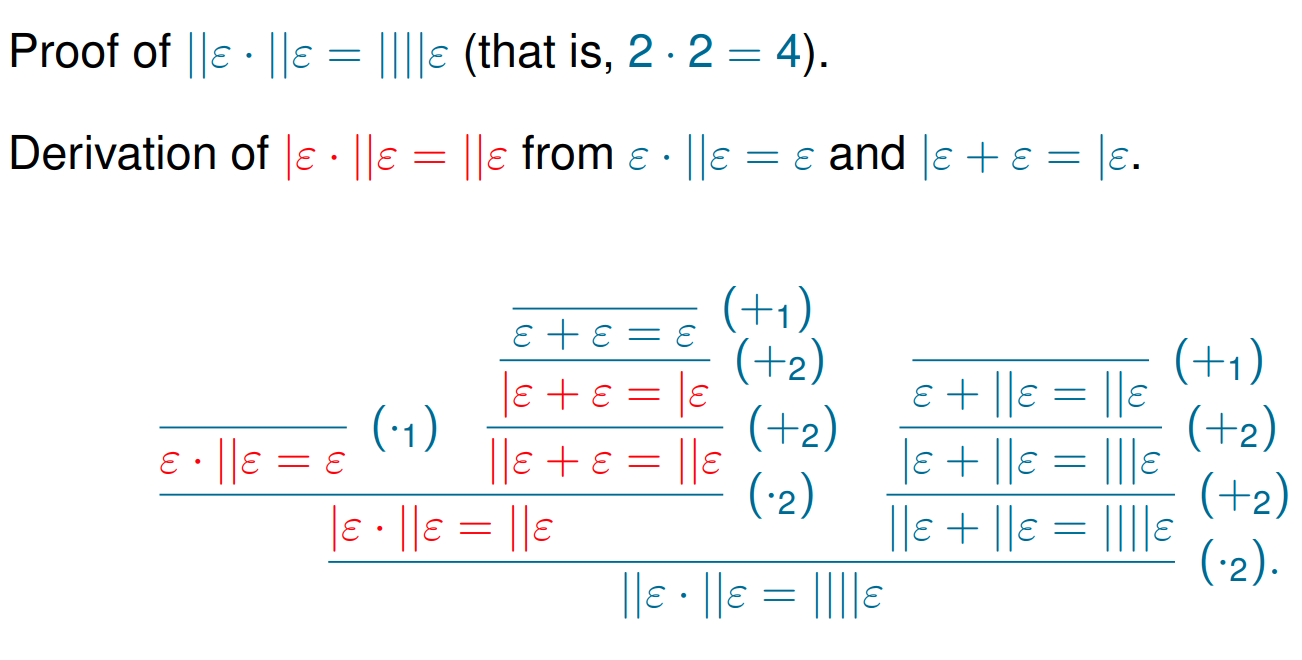

Proof, Derivation in this Inference System

Arbitrary First-Order Formulas

- A first-order signature (vocabulary): function symbols (including constants), predicate symbols. Equality is part of the language.

- A set of variables.

- Terms are built using variables and function symbols. For example, .

- Atoms, or atomic formulas are obtained by applying a predicate symbol to a sequence of terms. For example, or .

- Formulas: built from atoms using logical connectives and quantifiers . For example,

Clauses

- Literal: either an atom or its negation .

- Clause: a disjunction of literals, where .

- Empty clause, denoted by : clause with 0 literals, that is, when .

- A formula in Clausal Normal Form (CNF): a conjunction of clauses.

- From now on: A clause is ground if it contains no variables.

- If a clause contains variables, we assume that it implicitly universally quantified. That is, we treat as .

Binary Resolution Inference System

The binary resolution inference system, denoted by is an inference system on propositional clauses (or ground clauses).

It consists of two inference rules:

- Binary resolution, denoted by BR:

- Factoring, denoted by Fact:

Soundness

- An inference is sound if the conclusion of this inference is a logical consequence of its premises.

- An inference system is sound if every inference rule in this system is sound.

- is sound.

- Consequence of soundness:

- let be a set of clauses.

- If can be derived from in , then is unsatisfiable.

Example

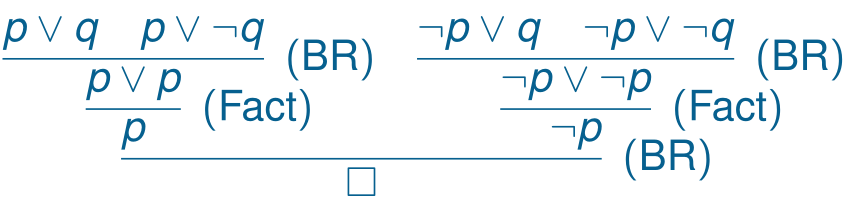

Consider the following set of clauses:

Is S unsatisfiable?

The following derivation derives the empty clause from this set:

Hence, this set of clauses is unsatisfiable.

Exercise

Consider the following set of clauses:

Show that there exists an infinite number of different derivations of the empty clause from the clauses of .

Can this be used for checking (un)satisfiability?

- What happens when the empty clause cannot be derived from ?

- How can one search for possible derivations of the empty clause?

- Completeness.

- Let be an unsatisfiable set of clauses.

- Then there exists a derivation of from in .

- Let be an unsatisfiable set of clauses.

- We have to formalize search for derivations.

However, before doing this we will introduce a slightly more refined inference system.

Selection Functions

A literal selection function is a function that selects literals in a clause.

- If is non-empty, then at least one literal is selected in .

We denote selected literals by underlining them, e.g.,

- Note: selection function does not have to be a function.

- It can be any oracle that selects literals.

Binary Resolution with Selection

We introduce a family of inference systems, parameterised by a literal selection function .

The binary resolution inference system, denoted by , consists of two inference rules:

- Binary resolution, denoted by

- Positive factoring, denoted by :

Completeness?

Binary resolution with selection may be incomplete, even when factoring is unrestricted (also applied to negative literals).

Consider this set of clauses:

It is unsatisfiable:

Note the linear representation of derivations (used by Vampire and many other provers).

However, any inference with selection applied to this set of clauses give either a clause in this set, or a clause containing a clause in this set.

Literal Orderings

Take any well-founded ordering on atoms, that is, an ordering such that there is no infinite decreasing chain of atoms:

In the sequel will always denote a well-founded ordering.

Extend it to an ordering on literals by:

- If , then and ;

- .

Example: Given . What is the extended ordering on literals?

Exercise: prove that the induced ordering on literals is well-founded too.Orderings and Well-Behaved Selections

Fix an ordering . A literal selection function is well-behaved if either

- a negative literal is selected,

- all maximal literals (w.r.t ) must be selected in C.

To be well-behaved, we sometimes must select more than one different literal in a clause. Example: or .

Completeness of Binary Resolution with Selection

Binary resolution with selection is complete for every well-behaved selection function.

Consider our previous example:

A well-behave selection function must satisfy:

- , because of

- , because of

- , because of

There is no ordering that satisfies these conditions.

Example

Let be boolean atoms and let be the following set of ground formulas:

Take any ordering such that p ≻ q and any selection function over such that

(a) Is a well-behaved selection function over ? (b) How many inferences of are applicable to ?